Multiple-choice tests are usually seen as a less-than-desirable form of student assessment, but in some contexts (especially large classes) we find ourselves relying on these types of questions. Creating effective multiple-choice questions takes time and effort, but will be better indicators of student knowledge and understanding. In this blog post, I will provide some “best practices” that have helped me in creating effective multiple-choice questions for my assessments.

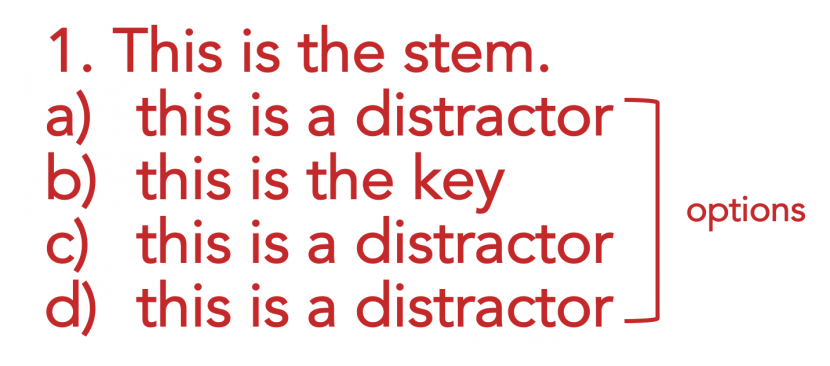

The Anatomy of the Multiple-Choice Question

Two Important Concepts

Validity and Cognitive Load

In this context, validity is the extent to which a multiple-choice question accurately measures a student’s knowledge of the topic or learning objective being assessed. Basically, does the student’s response to a multiple-choice question really indicate their mastery of that knowledge?

Cognitive load is a concept proposed by John Sweller (1988) and refers to the amount that one’s working memory can hold at one time. When applied to assessments, it’s recommended that we should avoid overburdening learners with extra activities that can tax their resources needlessly and that don’t directly contribute to learning.

Five Best Practices for Writing Effective Multiple-Choice Questions

1. Clear Stems

Don’t try to double-up or overload a MCQ with multiple learning objectives. This doesn’t mean you should “dumb down” your questions – you should, of course, you should write your MCQs according to the level of learning you’re assessing (e.g., Bloom’s Taxonomy). But you can create some high-level MCQs which really test your learners’ mastery of the topic while still only assessing one learning objective.

Outside of testing vocabulary which is integral to the course content, you should also avoid overly complex language that isn’t related to the learning objective (Albedi & Lord, 2001). This can affect your validity (what are you really testing?) and cognitive load (learners gets caught up in not knowing the vocabulary which inhibits their ability to demonstrate their knowledge of the content.) This is also a concern for additional language students.

Using negatives in your stem (like not, never, except) can do the same; I recommend that you use them sparingly and with specific purpose, and always highlight the negative term (and NEVER use them in binary questions like true/false.)

It’s also recommended that you use direct questions in your stems rather than statements with blanks. But if you want to use a blank, your learners’ cognitive load will be less taxed if you put it at the end.

2. Plausible Distractors

Distractors should be plausible and based on the misconceptions and mistakes commonly made by students. This means that they can be diagnostic – what the student chooses will tell you something about what they know/don’t know, where they’re going wrong, etc.

Avoid ‘all of the above’ or ‘none of the above’ distractors. These don’t really tell you much and allow students to guess more easily.

Also avoid “throw away” distractors, which are ones that students can easily disregard because of they obvious implausibility. All of this will increase the validity of your test.

3. Number of Distractors

When it comes to the number of options, use what make sense for the question. Varying the number of options between questions (3, 4, 5, etc.) will not greatly impact the assessment and although four seems to be very common, three is often adequate (Rodriguez, 2005).

It’s difficult to write a lot of plausible distractors, so don’t force yourself and add “throw away” distractors, lead to validity issues (as discussed above.)

4. Copying and Pasting

Although we’re all short on time and energy, and writing effective multiple-choice questions isn’t easy, avoid copying and pasting language or content from the textbook or class notes. What you’ve reused might rely too much surrounding context, making it difficult for students to fully understand the questions (Parks & Zimmaro, 2016), or a student’s memory might simply be jogged by having read exactly that before, and not because they really know it. Both cognitive load and validity are affected by this practice.

5. Option Word Length

Without really realizing it sometimes, we tend to make the correct answer (the key) the longest option. This leads to something called cueing – we unwittingly signal to the learner what the correct answer is. Try to keep all options (distractors and key) around the same length so that your test maintains its validity.

Other Tips

Here are a few other tips and tricks to keep in mind when writing MCQs:

- Present options vertically rather than horizontally

- Use numerals for stems and letters for options (Haladyna, Downing & Rodriguez 2002)

- Use humour sparingly and only if it’s already part of your teaching style

- Avoid complex MCQs (“Type K”) (Albanese 1982) (e.g., both (a) and (b); (a), (b), and (c); (c) and (d), etc.)

- Consider other questions types, like matching and ordering

If you want to learn even more about writing effective multiple-choice questions, check out the scholarship in the resources below.

References

Albanese, M. A. (1982). “Multiple-choice items with combinations of correct responses: A further look at the Type K format.” Evaluation & the Health Professions, 5(2), pp. 218–228. doi: 10.1177/016327878200500207.

Albedi, J. & Lord. C. (2001). “The language factor in mathematics test.” Applied Measurements in Education, 14(3), 219-234.

Brady A. M. (2005). “Assessment of learning with multiple-choice questions.” Nurse education in practice, 5(4), 238–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2004.12.005

Downing, S.M. (2005). “The effects of violating standard item writing principles on tests and students: The consequences of using flawed test items on achievement examinations in medical education.” Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 10(2), 133–143.

Haladyna, T. M., Downing, S. M., & Rodriguez, M. C. (2002). “A review of multiple-choice item-writing guidelines for classroom assessment.” Applied Measurement in Education, 15(3), 309–334. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324818AME1503_5.

Park, J. & Zimmaro, D. (2016). Learning and assessing with multiple-choice questions in the college classroom. New York: Routledge.

Rodriguez, M.C. (2005). “Three options are optimal for multiple-choice items: A meta-analysis of 80 years of research.” Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 24(2), 3-13.

Leave a Reply